The MV Explorer docked in Scotland at a momentous time in the country’s history: In just two short months, on September 18, 2014, residents will vote in a milestone referendum to determine whether Scotland will remain a part of the United Kingdom or become an independent sovereign state, as it last was in 1707. The simple question being put to vote in 65 days is, “Should Scotland become an independent country?”

Understandably, this forthcoming vote — which is open to all British, Commonwealth and EU citizens age 16 and up currently residing in Scotland — has dominated the conversation in the country since arrangements for the referendum were set forth in early 2013. Those who support the “Yes Scotland” campaign led by the Scottish National Party firmly believe that Scotland would be better off with its own government separate from the current UK Parliament that oversees the United Kingdom’s (and therefore Scotland’s) foreign policy, defense, social security and immigration. Others who believe that Scotland and the UK are say that giving up Scotland’s association with the United Kingdom would lead to a decreased standard of living and that starting a brand-new government would ultimately send the country into financial ruin.

While current polls predict that the “No” vote will come out ahead, many of Scotland’s residents are still undecided whether they’ll vote for independence or not. Still, among those who hold staunch views on either side, the upcoming vote has pitted work colleagues, neighbors and family members against one another. “It is quite an emotive issue,” said Christine Reid, an interport lecturer affiliated with the University of Strathclyde Business School in Glasgow, who was named European Business Librarian of the Year in 2000. Christine joined the shipboard community for four days while we sailed from Spain to Scotland.

Historic context for the vote for independence

To help Semester at Sea voyagers better understand Scotland’s centuries-long, turbulent history with England, and to give some context to the current “vote for independence,” Christine gave a concise history of Scotland to a packed crowd in the ship’s Union one evening. In her talk, she described how “fate has a habit of stepping in and turning everything around” during Scotland’s political and royal past — beginning with Alexander III, an ancient Scottish king, who died in 1286 after falling from a horse, and whose heir, a princess of Norway, subsequently died when her ship sank en route to Scotland from Norway to assume the throne.

William Wallace (made famous in the Mel Gibson film Braveheart ‚Äì “the most historically inaccurate film ever made” says Christine) and Robert the Bruce became symbols of resistence during the Scottish wars of independence — which eventually led to England renouncing all claims of sovereignty over Scotland in 1328.

Scotland was independent for nearly 300 years until James VI of Scotland (the only son of Mary, Queen of Scots) who also became James I of England (when England’s Queen Elizabeth died without a direct heir) joined the two countries under the same monarch with the Union of Crowns in 1603. A century later, Scotland ‚Äì ultimately tired of fighting the English for so long and desperately needing economic stability ‚Äì merged governments with England to become Great Britain and to be governed under a Parliament of Great Britain based in the Palace of Westminster, dissolving the Scottish Parliament in 1707.

Fast forward more than two hundred years to 1999, by which time Scots had become generally dissatisfied with being governed by the UK Parliament in Westminster. A new Scottish Parliament was formed to oversee Scottish domestic “devolved” domestic concerns, including health, transportation, education, justice, housing and the environment. Fast forward again to 2011, when the Scottish National Party won a majority of seats in the relatively new Scottish Parliament; it was that political party, led by Alex Salmond, who put forward the current independence referendum now up for vote.

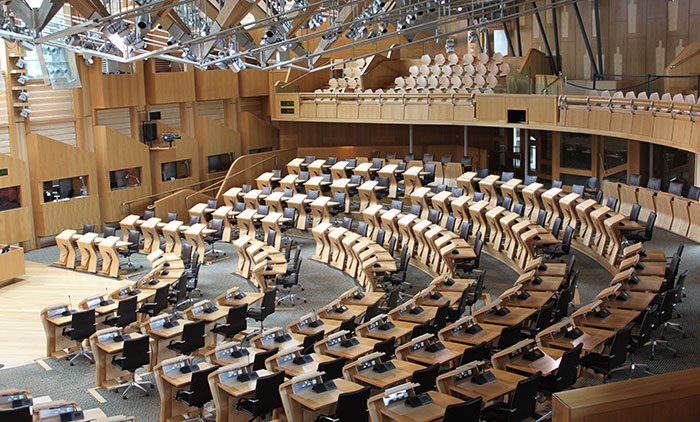

Dr. Iain Campbell, professor emeritus at the University of Pittsburgh and past professor and dean on several Semester at Sea voyages, is Scottish by birth, but unable to vote in the referendum since he moved out of the country several decades ago. While visiting his homeland this summer, he joined Bob Smith’s World Regional Geography class for a Field Lab to Edinburgh to visit the Scottish Parliament, learn more about how the current government operates, and talk about the referendum firsthand with Kezia Dugdale, a Labour Party Member of Scottish Parliament (MSP) fervently against Scottish independence.

Iain offered many firsthand anecdotes and insights into the current state of affairs of Scotland, including the fact that although England and Scotland have long been lumped together under Great Britain, they are geographically quite different. About 450 million years ago the land that is now England was on a totally separate continent, while Scotland was part of the ancient continent of Laurentia that also included North America and Greenland. (It was only after the continents moved toward each other, millions of years later, that the two landmasses formed Great Britain.) Ethnically, too, the English and Scottish are far apart, says Iain, with the English descending from the Anglo-Saxons and some ancient Norse, while the Scottish mainly come from ancient Picts and Gaels.

Pros and cons of Scottish independence

Geological and ethnic differences aside, those who want Scotland to become a nation independent of England say that taking control of the country’s finances ‚Äì and lowering the rate of corporate tax — would attract new businesses, leading to more jobs and economic stability. The “Yes” camp believes that Scotland would be able to use all of the oil revenues from Scotland’s North Sea and nuclear weapons would be removed from Scotland for good, the country would be able to remain in the European Union (since the UK is already a member).

Meanwhile, those who are against independence note that remaining in the EU isn’t necessarily a “done deal,” as the “new” independent Scotland might have to reapply to join. Plus, Scotland is part of the most successful economic, political and social union the world has ever seen, the Better Together campaign argues: “We have the best of both worlds: A Scottish Parliament with power over health and education, and we have the security of being one of the largest economies of the world.”

Christine Reid pointed out that the information coming from both sides of the debate is contradictory: “The SNP says one thing and campaign for other side says something completely different. It’s very, very difficult as a typical Scottish person to know who and what to believe.”

She continued, “At the beginning of 2013 we were told that as an independent country, we would be 6th wealthiest nation in world. In October, it was revised, when they said we’d be the 14th wealthiest. A couple months ago, official body came out and said, we’d be the 20th wealthiest. That’s just one example of how information is constantly changing.”

MSP Kezia Dugdale echoed Christine Reid’s sentiments: “We are often hearing two interpretations of the very same facts.” For example, Kezia said the Scottish National Party claims it would cost 200 million pounds to create a new government by 2016, while the “Better Together” campaign says it will be closer to 1 billion.

There are many unanswered questions that swirl around a potential “No” result, from whether UK would allow Scotland to continue to use the British pound as currency (as the “Yes” campaign contends) to whether the term “United Kingdom” would still even be used. “It wouldn’t be so united anymore, would it?” quipped Kezia.

Then there is the consideration of country borders: “Would current UK residents need a passport to cross from Scotland to England?” asked Kezia. “It’s definitely a possibility if Scotland determines it wants different immigration policies than England.”

MSP Kezia Dugdale will vote along her Scottish Labour Party lines, which is a solid “No.” She noted, “I enjoy the best of both worlds,” echoing the “Better Together” campaign cry. Further, she is a firm believer in spreading the wealth and redistributing it across the United Kingdom: “This way a rich banker in London can help support a poor single mom in Glasgow.”

In addition to casting her “No” vote, Kezia is simply looking forward to September 18 coming and going, in order to get back to business as usual. “We’ve been talking about this referendum for too long, instead of talking about more important issues facing our country,” including health, education, and technology.

As for Christine Reid, she said, “My heart says yes, because I’m a Scot. I’m a Scot first, and British second. But my head says no. In this day and age I think we are better being part of something bigger. We just have to look back at what happened to world in 2007-08 with the economic crisis. Could [Scotland] have survived? We would have been completely bankrupt, I think.”

And what do Bob Smith’s World Regional Geography students think? They were asked to cast a vote in class the day after they toured the Parliament building and met MSP Kezia Dugdale. Nineteen of the 21 students said that they would vote “No,” Scotland should not become an independent nation.

Though current polls in Scotland aren’t predicting that a “No” vote will emerge on top by such a landslide, that result does seem to be the way the tide is leaning. Certainly newly informed Semester at Sea students ‚Äì along with the rest of the world — will be tuned to news reports on September 19 once the important referendum votes are tallied.